Treatment of civilians deprived of their liberty

in the context of the armed attack by the Russian Federation against Ukraine

This report describes the treatment of civilians deprived of their liberty in the context of the armed attack of the Russian Federation against Ukraine since 2022.

It looks at two groups of civilians deprived of their liberty since 2022. First, at those detained by the Russian Federation in occupied territory, and second, at those detained by Ukraine on national security grounds. Scroll down for details on each group.

It builds on previous reports by the Mission and is based on interviews and other information collected between June 2023 and August 2025.

For information on the treatment of captured soldiers (who are called prisoners of war), see: 2024-10-01 OHCHR 40th periodic report on Ukraine.pdf.

I. What is the report about?

Anna's story

Anna's father, Roman, used to work for the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. He was detained in January 2023.

Anna does not know where her father is. All her attempts to find him were unsuccessful.

More than a year after her father’s disappearance, Anna received a response from the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation. The letter stated that her father was detained in the Russian Federation. That’s it. Later, responding to Anna’s attempt to get more information, the Ministry denied her father’s detention entirely.

Anna has had no contact with her father in over two and a half years.

Anna's story

Anna's father, Roman, used to work for the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. He was detained in January 2023.

Anna does not know where her father is. All her attempts to find him were unsuccessful.

More than a year after her father’s disappearance, Anna received a response from the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation. The letter stated that her father was detained in the Russian Federation. That’s it. Later, responding to Anna’s attempt to get more information, the Ministry denied her father’s detention entirely.

Anna has had no contact with her father in over two and a half years.

II. What is the basis for the findings of this report?

Data collected by the Mission for each group of civilians

-

Documented details on 508 cases of civilian detainees (392 men, 103 women, 3 girls, and 9 boys) based on interviews with victims, witnesses, family members, lawyers, public officials and analysis of official letters, court documents, photo, video and other available materials.

-

In 216 of those cases, OHCHR confidentially interviewed the detainees (152 men, 63 women and 1 boy) after they were released from captivity.

-

The Russian Federation has not granted the Mission access for independent monitoring in occupied territory despite repeated requests.

Civilian detainees held by the Russian Federation:

-

Conducted 409 confidential interviews (249 men, 146 women, 12 boys and 2 girls) in 17 official places of detention in 11 regions of Ukraine and with individuals after their release from detention.

-

Monitored 180 trial hearings in conflict-related cases.

-

Analysed more than 2 000 court cases relating to “collaboration” charges.

-

The Mission has regular and unimpeded access to conflict-related detainees in official places of detention in territory controlled by the Government of Ukraine.

Conflict-related detainees held by Ukraine:

The information was collected between 1 June 2023 and 10 September 2025.

III. What is the applicable international legal framework?

International humanitarian law (IHL)

The Fourth Geneva Convention, supplemented by Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, sets forth criteria and procedures governing the deprivation of liberty of civilians during armed conflict.

Most provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention apply to a specific group of civilians called “protected persons” – i.e. civilians “alien” in enemy territory, and civilians living in occupied territory.

International human rights law (IHRL)

IHRL applies to all categories of civilians deprived of their liberty and complements IHL.

Important human rights instruments for this context are the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Convention against Torture and the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

Key provisions include:

Despite some differences, IHL and IHRL law set out common minimum standards for the fair and humane treatment of civilians deprived of their liberty during conflict.

Torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment are absolutely prohibited and the life, well-being and dignity of persons deprived of their liberty must be respected.

01

Civilians can only be detained on lawful grounds and must be released from detention as soon as the lawful grounds of their detention cease to exist.

02

The decision to deprive a person of liberty should be applied as a measure of last resort; the decision must be made on an individual basis and be subject to regular review.

03

Individuals should have the possibility to challenge decisions to deprive them of their liberty.

04

Communication with the outside world should be made possible (some exceptions are however allowed).

05

Families should be provided with information on the fate and whereabouts of loved ones.

06

Independent monitors should have access to places of deprivation of liberty.

07

The use of unofficial places of detention places detainees outside of the protection of the law and increases the risk of abuse.

08

The deportation of protected persons from occupied territory is prohibited regardless of motive (this is only applicable in IHL).

09

IV. Civilian detainees held by the Russian Federation

Who: Ukrainian civilians.

What: Arrested, detained or interned by the Russian Federation.

Where: In occupied territory of Ukraine (including those later illegally transferred to the Russian Federation).

The report focused on civilians arrested, detained or interned for actions or reasons related to the armed attack

by the Russian Federation against Ukraine.

Ukrainian civilians on occupied territory of Ukraine are protected persons under the Fourth Geneva Convention

(see legal framework above).

Internment

Rule: Geneva Convention IV allows for internment of protected persons (i.e. take into administrative or security detention) as an exceptional measure, if the Occupying Power considers it necessary for imperative reasons of security. However, it requires that decisions regarding internment be made according to a regular procedure to be prescribed by the Occupying Power.

Application: The Mission is not aware of such a procedure established or applied by the Russian Federation in occupied territory of Ukraine.

Criminal detention

Rule: The Fourth Geneva Convention also sets out rules relating to penal legislation, procedure and treatment of detainees in criminal cases in occupied territory. As a general rule, the laws in force in the occupied territory, including the penal laws of the occupied territory and its regular court system, shall remain in force.

Application: The Russian Federation purported to illegally annex Crimea in March 2014 and the occupied areas of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia regions in September 2022. It imposed its own judicial and legal system on the occupied territory of Ukraine in violation of international law.

This report establishes that the Russian Federation has subjected Ukrainian civilian detainees to serious violations

of international humanitarian and human rights law:

1 of 6

Torture and ill-treatment, including sexual violence, have been applied in a systematic and widespread manner in places of detention.

2 of 6

Extrajudicial executions of Ukrainian civilians and deaths in custody because of torture, inhuman conditions of detention and deprivation of medical care have taken place.

3 of 6

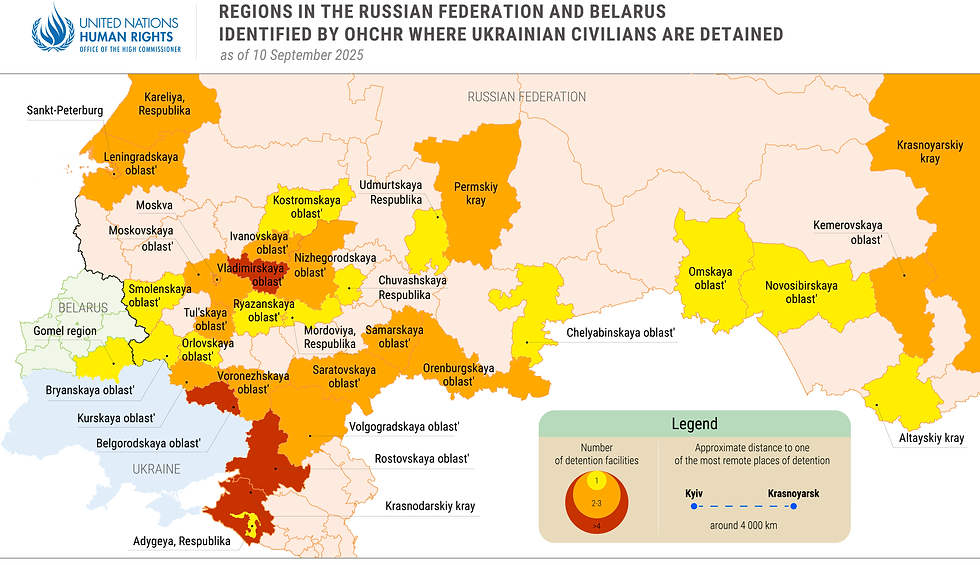

Frequent violations of safeguards have resulted in arbitrary detention, and in a significant number of cases appear to amount to enforced disappearances. This leaves family members in anguish, not knowing the fate of their loved ones.

4 of 6

Patterns of targeting specific groups, such as family members of persons suspected of links to Ukrainian armed forces, human rights defenders, journalists, public officials, teachers, people who express “pro-Ukrainian views” or employees of critical infrastructure.

5 of 6

The cumulative effect of these measures, combined with a lack of accountability, has placed many Ukrainian civilians outside the protection of the law during their detention.

6 of 6

High numbers of Ukrainian civilian detainees remain arbitrarily detained in occupied territory of Ukraine and the Russian Federation for reasons or actions related to the armed conflict, often held in dire conditions, without the possibility of relief.

Key recommendations to the Russian Federation

1 of 9End extrajudicial execution, torture, ill-treatment and sexual violence against civilian detainees and ensure humane conditions in all places of deprivation of liberty.

Key recommendations to the Russian Federation

2 of 9Conduct a systematic review of the cases of Ukrainian civilians detained in relation to the armed conflict, and unconditionally release them as soon as the lawful reasons for their deprivation of liberty cease to exist.

Key recommendations to the Russian Federation

3 of 9Conclude practical arrangements for the release, repatriation, and return to places of residence for civilians detained in relation to the armed conflict, taking into account humanitarian considerations.

Key recommendations to the Russian Federation

4 of 9Ensure effective implementation of safeguards for Ukrainian civilian detainees.

Key recommendations to the Russian Federation

5 of 9Criminalize torture in line with international law and conduct timely and effective investigations into all allegations of wrongdoing.

Key recommendations to the Russian Federation

6 of 9Cease the practice of deporting detainees to detention facilities in the Russian Federation.

Key recommendations to the Russian Federation

7 of 9Establish an official Information Bureau which collects, centralizes and transmits the relevant information on the fate and whereabouts of Ukrainian civilians who have been deprived of their liberty by the Russian Federation.

Key recommendations to the Russian Federation

8 of 9Encourage the wide use of communication means between those deprived of their liberty and their families.

Key recommendations to the Russian Federation

9 of 9Provide independent monitors, in particular the ICRC, full and regular access to all places where Ukrainian civilian detainees are held.

Key recommendations to the international community

1 of 3Continue to request access for independent human rights monitors, including the ICRC and OHCHR, to detainees in the hands of the Russian Federation

Key recommendations to the international community

2 of 3Support steps to conclude agreements for the release, repatriation and return to places of residence for civilians detained in relation to the armed conflict.

Key recommendations to the international community

3 of 3Provide adequate funding and support for services for survivors of torture and sexual violence of all genders.

Olha's story

Olha has a 27-year-old daughter named Dariia. Dariia lived in occupied Kherson region and took care of her grandmother.

After the occupation, Dariia was detained twice for short periods. Then she was detained again in October 2024. Olha did not know anything about her daughter’s whereabouts for 1 ½ months after her detention, and she still cannot talk to her.

Dariia had a mini-stroke, which is especially worrying for her mother. In letters, Dariia has described her deteriorating health. Medication sent by her family has not reached her.

A Russian-appointed court in occupied territory found Dariia guilty of high treason and sentenced her to 12,5 years of imprisonment and two years restriction of liberty

Vira's story

Vira lived in occupied Luhansk region. Since her childhood, Vira has a vision impairment. In September 2023, armed men wearing masks came to Vira’s home and arrested her. Vira described that she spent almost one year in a detention facility in Luhansk. The walls of her cell were covered with mold; the window was broken and could not be closed, even in winter. The cell had cockroaches, and sometimes rats came out of the sewage system. The food was impossible to eat.

While detained, Vira underwent interrogation, during which she was tied to a chair, subjected to electric shocks and threatened. She signed a pre-prepared confession. On this basis, the occupying authorities prosecuted her for attempted murder of an official of the former self-proclaimed ‘Luhansk people’s republic.’ She was sentenced to 15 years of prison.

She was released during a POW exchange in September 2024.

V. Conflict-related detainees

held by Ukraine

“Operatives of the Security Service tied my arms and legs to a chair with plastic straps, hit my face, applied electroshocks to my legs and burnt my left leg with a cigarette. Afterwards, they ordered me to say on video that I got these injuries as a result of an accident”

– male conflict-related detainee on his interrogation before entering an official place of detention.

“During the arrest, I was thrown against a wall. My head and arm really hurt, but the doctor told me ‘not to complain’”

– woman conflict-related detainee on the medical check-up upon admission to a temporary

detention facility.

Who: The vast majority of conflict-related detainees have Ukrainian nationality. That is, they are citizens detained in their own country. Only very few are Russian citizens.

What: Detained in conflict-related criminal cases on charges related to national security. National security-related charges cover a wide range of criminal offenses, many of which involve serious and harmful acts, such as treason and sabotage. It also covers collaboration cases.

Where: In pre-trial detention centers and penal colonies in Government-controlled territory of Ukraine.

Collaboration cases:

Many conflict-related criminal cases involve charges of collaboration with the Russian occupying authorities, an offence introduced into the Criminal Code in March 2022. The law defines collaboration as covering a broad range of activities.

The Mission previously documented that some individuals have been prosecuted for collaboration because they carried out ordinary work for the benefit of the community, which can be lawfully compelled by the occupying authorities under international humanitarian law. For instance, people were prosecuted for working in emergency services, construction, water services, humanitarian relief and garbage removal under occupation.

For further details on human rights concerns in collaboration cases, please see: 2024-03-20 OHCHR Report on Occupation and Aftermath_EN.pdf

Ukraine detains individuals in conflict-related cases based on the applicable provisions of its Criminal Code and Criminal Procedure Code. The detention of a State’s own nationals during armed conflict is primarily regulated by international human rights law.

While Russian citizens benefit from the protection of the Fourth Geneva Convention as protected persons, Ukraine also applies its national criminal legislation when detaining Russian citizens.

Since the full-scale invasion by the Russian Federation, the increased number of conflict-related detainees has placed an additional burden on the criminal justice system of Ukraine. While authorities have taken steps to ensure procedural safeguards and improve detention conditions, some concerns remain. Key concerns include:

1 of 4

The Mission continued to document cases of torture and ill-treatment of conflict-related detainees by Ukrainian authorities. They often happened during initial hours of detention.

2 of 4

Pre-trial detention is commonly applied and extended over lengthy proceedings.

3 of 4

Accountability for violations against conflict-related detainees remained limited.

4 of 4

Several measures taken by Ukrainian authorities with a view to supporting diplomatic efforts to release its citizens from detention by the Russian Federation raised human rights concerns, in particular in relation to free and informed consent of Ukrainian nationals released to the Russian Federation and the prohibition of refoulement.

The accession process to the European Union offers an opportunity to analyze comprehensively the risk factors and strengthen safeguards in the penitentiary system for torture and ill-treatment in line with a human rights-based approach and ensure accountability for such violations.

Key recommendations

to Ukraine

1 of 5Ensure that conflict-related detainees are treated in full compliance with international law, including in particular by protecting them from torture, ill-treatment and sexual violence at all stages of deprivation of liberty

Key recommendations

to Ukraine

2 of 5Conduct timely and effective investigations of all allegations of arbitrary arrests, detention, torture or ill-treatment in the context of prosecution of conflict-related crimes.

Key recommendations

to Ukraine

3 of 5Ensure that all efforts to return civilian detainees from Russian captivity protect the rights of all persons affected by this process, in compliance with IHL and IHRL.

Key recommendations

to Ukraine

4 of 5Use pre-trial detention as a measure

of last resort.

Key recommendations

to Ukraine

5 of 5Strengthen reporting and complaint systems and collection of data on complaints.

Key recommendations to the international community

1 of 2Provide targeted and sustained financial support to strengthen Ukraine’s penitentiary system, in light of the increased burden caused by the armed conflict.

Key recommendations to the international community

2 of 2Support capacity-building and training programmes (i) for penitentiary staff on international human rights standards, and (ii) for medical personnel working in detention settings on identification, documentation and reporting on torture and ill-treatment, in line with the Istanbul Protocol.